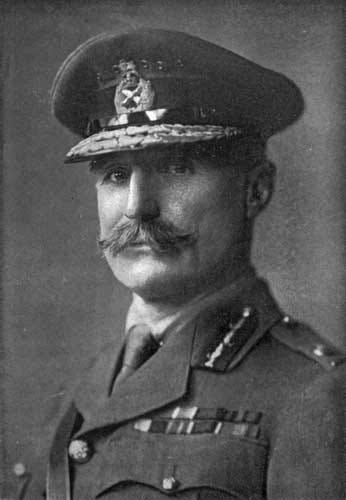

General Sir Ian Hamilton - British Army

16 January 1853 – 12 October 1947

Born on the island of Corfu. Slender, courtly, Hamilton did not look the part of a general officer. Prime Minister Asquith thought Hamilton had ”too much feather in his brain”.1 A war correspondent wrote that Hamilton had "a breadth of mind which the army in general does not possess". Author of a novel, Hamilton also wrote poetry - definitely not the run of the mill British General Officer. Hamilton attended Sandhurst (the British West Point) in 1870 after which he saw action in Afghanistan with the Gordon Highlanders.

Hamilton was a product of ‘small’ colonial wars fought by a professional army. Taken prisoner at the Battle of Majuba during the Boer War, Hamilton was sent back to England to recuperate then took part in the Nile Expedition of 1894-1895. In Burma (1886–1887) he was made Lt. Colonel then Colonel in 1891 while campaigning in Bengal. Hamilton was wounded during the Chitral Campaign in 1898.

The Second Boer War (11 October 1899 – 31 May 1902) was a different matter. Here the new Colonel established a reputation as a ‘comer’ winning promotion to Major General and a Knight of the Bath. His march from Bloemfontein to Pretoria was chronicled by Winston Churchill, then a war correspondent. ‘Hamilton travelled 400 miles from Bloemfontein to Pretoria fighting 10 major battles with Boer forces… and fourteen minor ones, and was recommended “twice for the Victoria Cross - but on the first occasion was considered to young and on the second too senior¨ 2 In his first assignment with Kitchener, the Sirdar wrote “At much personal convenience, Lord Roberts lent me his Military Secretary, Sir Ian Hamilton, as my Chief of Staff. His high soldierly qualities are already well known, and his reputation does not require to be established now. I am much indebted to him for his able and constant support to me as Chief of Staff, also for the marked skill and self-reliance he showed later, when directing operations in the Western Transvaal.¨3

Hamilton was Military Attache of the British Indian Army in Manchuria during the Russo Japanese War, important because weapons and tactics were used in a war that saw the first victory of an Asian army over a European.

With the coming of the First World War Hamilton was Commander of the Home Army, at the height of reputation, a successful leader. But,¨Whilst a senior and respected officer, perhaps more experienced in different campaigns than most, Hamilton was considered too unconventional, too intellectual, and too friendly with politicians to be given a command on the Western Front.”4

In March 1915,Hamilton was made Commander of the Gallipoli Campaign - an effort to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war. He recounts, “Next morning, that is the 12th instant, I was working at the Horse Guards when, about 10 a.m., K. (Field Marshall Herbert Kitchener) sent for me. I wondered! Opening the door I bade him good morning and walked up to his desk where he went on writing like a graven image. After a moment, he looked up and said in a matter-of-fact tone, "We are sending a military force to support the Fleet now at the Dardanelles, and you are to have Command." 5

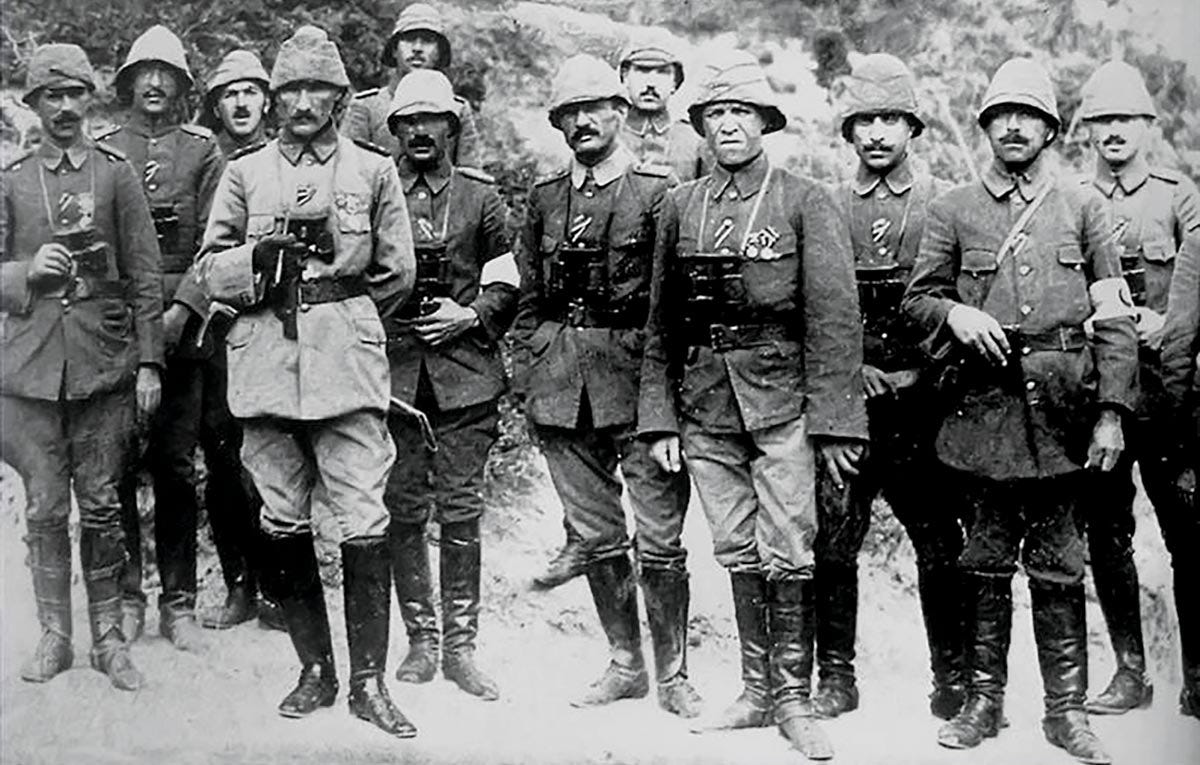

Incredibly, “Hamilton was not given a chance to take part in planning the campaign.” Knowledge of Turkish positions on the Gallipoli Peninsula was poor. Liman von Sanders, a German General Officer advising the Turks was an unknown quality soon recognized, along with Mustafa Kemal as a formidable opponent.

The initial Naval assault nearly carried the waters off Gallipoli but three pre- dreadnought battleships were lost in the attempt; Admiral de Roebeck could not see the open door to the Sea of Marmara.

The initial landings,suffering heavy losses at Anzac Cove and Cape Helles were plagued by instances of indecision reflecting muddled command arrangements and a commander that did not have the force of character to change the course of the campaign. His command post at Mudros on the Island of Lesbos became a purgatory - Hamilton’s orders were often irrelevant by the time they reached Gallipoli and his superior, Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, did not provide troops and ammunition as needed. Gallipoli cost him his reputation as well as Hamilton’s. George Patton later made a comment to the effect that had the commanders changed sides defeat would have turned into victory. The Allies withdrew from Gallipoli on January 9, 1916 in the best executed maneuver of the campaign.

Hamilton was recalled on October 16,1915 - his ineptness was the end of his career. A prolific writer, a later admirer of Hitler (defended by Ian Kershaw), Hamilton was a highly intelligent man versed in liberal arts and up to Gallipoli a fine soldier.

Sources

Cassar, George H., Asquith as a War Leader

Carlyon, Les, Gallipoli

Hamilton,Ian, Gallipoli Diary, Volumes 1 & 2, Musaicum Books 2021

Notes

1.Cassar,George H., Asquith as a War Leader P. 78

2. Carlyon, P.17

3."No. 27459". The London Gazette. 29 July 1902. P.4835

4.Carlyon P. 16-17

5.Hamilton, Ian, Gallipoli Diary, Page 23

In plain words, this almost seems to be a set-up. This shows how little technical failings drown even the biggest of Generals through no fault of their own.